Introduction

The Common and Emerging Practices, a new series of resources from the Impact Principles, aims to capture key insights from notable trends in common practices in implementing the Impact Principles by our Signatories and highlight promising emerging practices and key gaps. By sharing these common and emerging best practices in impact management, we seek to elevate impact practice in the market and ensure that capital is mobilized at scale with integrity to drive meaningful impact outcomes.

The resources related to Common and Emerging Practices will be released in phases through website publication of initial drafts for each of the nine principles in series, followed by draft and final consolidated reports with stakeholder engagement.

Principle 1

Define strategic impact objective(s), consistent with the investment strategy

The Manager shall define strategic impact objectives for the portfolio or fund to achieve positive and measurable social or environmental effects, which are aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), or other widely accepted goals. The impact intent does not need to be shared by the investee. The Manager shall seek to ensure that the impact objectives and investment strategy are consistent; that there is a credible basis for achieving the impact objectives through the investment strategy; and that the scale and/or intensity of the intended portfolio impact is proportionate to the size of the investment portfolio.

The Components of Principle 1

- Define strategic impact objectives for the portfolio or fund, aligned with the SDGs or other widely accepted goals

- Ensure impact objectives and investment strategy are consistent

- Ensure credible basis for achieving the impact objectives

- Ensure proportionate scale and/or intensity of the intended portfolio impact

Overview

Principle 1 highlights the foundational role of clearly defined strategic impact objectives in anchoring credible impact investment strategies and activities. Establishing impact objectives at the outset creates a strategic north star that can guide and strengthen decision making throughout investment processes and support continuous learning and improvement as well as organizational accountability.

The principle calls on impact investors to define impact goals at the portfolio- or fund-level that are aligned with widely accepted goals such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This steers investors away from fragmented impact efforts focused on individual investments and toward intentional contributions to address broader, systemic challenges that require coordinated and impact-aligned capital deployment at scale. Importantly, it also emphasizes that the impact objectives should be consistent with the investment strategy, ensuring that capital is deployed in a way that credibly contributes to intended impact outcomes. Moreover, the size and intensity of the intended portfolio impact should be proportionate to the size of the investment, ensuring that the impact is both meaningful and attainable.

Challenges in the Implementation of Principle 1

Principle 1 has gained broad adoption across the impact investing field, with defining strategic impact objectives becoming table stakes for most investors claiming impact. While this practice is widespread, there remain areas for improvement in implementation as investors go beyond surface-level objectives to develop deeper impact strategies, including deepening rigor and evidence of their theories of change and determining appropriate impact scale and intensity for the portfolio.

- Aligning with widely accepted goals without deeper strategic focus. While identifying SDGs or other widely accepted goals is a positive step to signal alignment with global priorities for positive impact, it risks stopping at a superficial mapping exercise if not supported by clear outcome objectives and meaningful strategies for driving investors’ decision-making. Investors create more strategic clarity by developing specific impact frameworks and metrics and using SDGs or other global or industry goals as a strategic lens to anchor impact objectives, track outcomes and guide capital deployment.

- Lacking rigor and evidence in theory of change. Many investors develop and share their theories of change or impact theses for how their funds or portfolios will contribute to desired outcomes. (See more on Key Observations below.) However, sometimes, these theories of change lack sufficient rigor and fail to articulate existing evidence, risks or underlying assumptions, or rely on assumptions without testing them, which limit their credibility and ability to improve over time.

- Establishing a credible basis for impact. Substantiating the link between a specific investment strategy and a set of impact objectives is not always straightforward, and the link is often assumed without clear explanation. Investors generally describe asset classes, stages of capital, specific investment terms, structures or design features that they believe are well-suited for delivering the intended outcomes. However, there is limited industry-wide knowledge or consensus documenting and correlating the effectiveness of specific investment strategies with types of impact objectives. This presents a potential knowledge-development agenda for the field, with increasingly diverse investment strategies being applied for impact.

- Determining “proportionate scale and intensity” of impact: Without clear benchmarks, norms or structured approaches in the field, it is difficult to determine the appropriate scale and intensity of intended impact relative to the size of the investment portfolio. The trade-offs between scale and intensity or breadth and depth of impact further complicate the issue.

Key Observations in the Implementation of Principle 1

Today, most investors claiming impact include some articulation of strategic objectives at the fund or portfolio level, making Principle 1 a cornerstone of credible impact investing. As the field matures, however, what distinguishes leaders is not simply whether they state impact goals, but how they define, operationalize and adapt those goals across increasingly complex portfolios and market environments. The Signatory disclosure statements also show different types of strategic orientations among investors that demonstrate how investors define their role and contribution to impact in the market, articulated in their theories of change.

Notable observations include:

1. Broad adoption of SDGs as global impact framework. The SDGs have become the prevailing global reference for articulating impact objectives, with most investors aligning their investments to one or more of the 17 SDGs, and some investors further aligning with one or more of the 169 SDG targets. This provides a shared language for the industry in allocating capital towards global impact priorities. Other frequently cited global frameworks include the 2X Challenge and Paris Accords, which address gender and climate impacts, respectively.

2. Aligning impact across diverse and multi-asset portfolios. As the field is maturing, more investors are moving beyond single-strategy funds to develop multi-asset, multi-strategy platforms where impact is applied across diverse asset classes, themes and geographies through multiple portfolios or funds. This is a promising trend that signals further mainstreaming of the impact investing field while expanding impact investors’ potential for innovation, flexibility and scale. These investors often develop an overarching firm-level impact framework — such as SDG alignment, impact thematic priorities or taxonomies — that provides strategic coherence across a diverse portfolio while allowing for tailored objectives at the strategy, theme or asset class levels. Impact objectives are adapted to fit the characteristics of private equity, private credit, real assets or public markets, reflecting variations in investment terms, processes and scale of these asset classes as well as differences in how impact is structured, delivered and measured within each strategy. When aligned effectively, this approach supports both strategic consistency and operational flexibility.

3. Theory of change to enable robust impact framework. The theory of change is increasingly recognized as a vital tool for bringing strategic clarity, accountability and intentionality to impact frameworks as investors move from high-level intentions to structured, evidence-based practices throughout the investment lifecycle. Theories of change help investors

- Clearly define the problems being addressed, including key affected stakeholders and root causes or structural barriers to the challenges.

- Articulate the contributions the investor will make, along with evidence supporting the strategy interventions.

- Map how the investment activities (inputs, activities) will drive short-term, intermediate and long-term changes (outputs, outcomes, impact).

- Identify assumptions, contexts and risks that may affect the path to impact.

4. Strategic orientation archetypes. As more investors articulate their theories of change across diverse markets, sectors and asset classes, a set of archetypes are emerging that reflect distinct approaches to impact ambition and value creation. These archetypes may be grouped into three broad categories:

- Solution-driven: Focused on identifying or scaling interventions that directly address a well-defined social or environmental problem.

- Financing-driven: Focused on how the type or structure of capital can address market gaps, de-risk investments or enable capital flow at scale.

- Systems change-driven: Focused on driving transformations at the sectoral, value chain or capital market level to address root causes and shift systems.

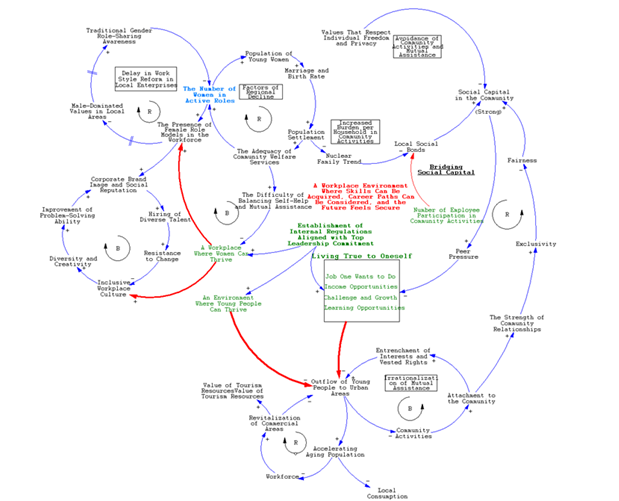

Many investors combine elements of these archetypes, but distinguishing between them can sharpen strategic clarity and enhance impact management [See Exhibit 1a].

Exhibit 1a. Theory of Change (ToC) Archetypes Based on Different Strategic Orientations of Investors

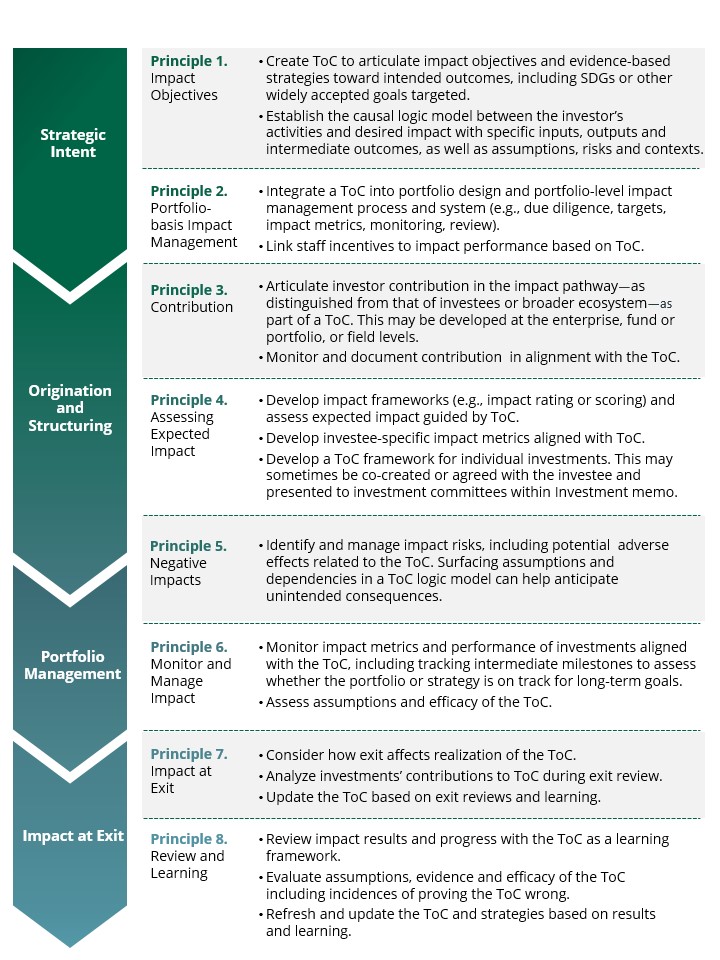

Exhibit 1b. Theory of change (ToC) Across the Principles and Investment Lifecycle

6. Theory of change at varying levels. Investors are developing and applying theory of change frameworks at various levels of decision making, including at the firm-wide level, fund or strategy level, asset class level, impact theme or sector level, and investment level. Some organizations develop nested theories of change at multiple tiers within the organization, including for each investment, to support flexible and rigorous application across their varying impact activities while ensuring alignment with overarching impact goals. This tiered approach allows for strategic clarity and consistency without over-simplification.

7. Institutional mandate as a driver of strategic objectives. Institutional investors with public or mission-driven mandates (e.g., development financial institutions, public or multilateral development banks, sovereign wealth funds, philanthropic or nonprofit investors) often define impact objectives directly tied to their institutional long-term missions, such as inclusive growth or climate resilience. These mandates provide long-term stability and clear guardrails for strategy, while also raising the bar for transparency and performance.

8. LPs aligning impact with managers. Asset owners and allocators (i.e., limited partners or LPs) depend on their asset managers (i.e., general partners or GPs) for their ability to deliver on their impact goals, making LP-GP alignment on impact a strategic and operational necessity. LPs also play an influential role in signaling the market on impact priorities as well as reinforcing impact integrity with alignment on impact standards and norms. Leading LPs are engaging with fund managers to align on impact goals and practices at the fund level. This may involve clarifying impact expectations during manager selection and in requests for proposals, including shared impact objectives and alignment with industry standards and frameworks (e.g., Impact Principles, SDGs, SFDR); agreeing on impact metrics and reporting expectations; engaging with GPs as partners through capacity building or co-creation of theories of change or impact frameworks; and using disclosures, verification or other third-party assurance, evaluation or benchmarking tools to track impact alignment and support continuous learning and improvement.

Common, Emerging and Nascent Practices in the Implementation of Principle 1

Note: The findings and observations are primarily based on analysis of the most recently published 166 Signatory disclosure statements at the time of the review in early to mid-2024.

An analysis of Signatory disclosures reveals a universal commitment to defining strategic impact objectives, including a widespread alignment with the SDGs and articulation of high-level investment strategies such as asset classes. However, beyond these broad commitment and strategic alignments, the depth, rigor and consistency in implementation of Principle 1 vary significantly. Just over one half of Signatories disclosed developing and using a theory of change or impact thesis, which indicate a more robust and structured approach to defining and operationalizing the impact objectives. Assessing the proportionality of impact scale and intensity relative to the size of capital is still a nascent practice disclosed by only a small subset of Signatories.

Common Practices

(50 to 100% of disclosures)

- Defining strategic impact objectives. 100% disclosed having strategic impact objectives, typically at the organization, fund or portfolio levels. These objectives range from broad thematic or sector-based goals (e.g., sustainable agriculture, financial inclusion, health, social equity) to targeting specific outcomes (e.g., job creation, reducing emissions, mobilizing impact capital in emerging markets) aligned with global frameworks such as the SDGs.

- Investment strategies consistent with impact objectives. 98% disclosed investment strategies — typically information about asset classes, investment stages and geographies — to establish how they are consistent with the impact objectives. 95% disclosed investing in private markets (e.g., private equity, venture capital, private debt, real estate, infrastructure) while 12% disclosed investing in public markets (e.g., green or social impact bonds, listed debt, listed equity), with a small but increasing number of Signatories investing across both public and private markets.

- Aligning with SDGs or other global impact frameworks. 84% disclosed aligning with one or more of the 17 SDGs, with some further specifying which of the 169 SDG targets they align with. Most investors identified between 4 and 10 SDGs they aligned with across their portfolio — often across multiple funds, strategies and asset classes — with many investors also identifying a smaller subset of primary SDGs that they specifically target for their impact objectives. Goal 8: Decent work and economic growth and Goal 13: Climate action were the most frequently targeted, while Goal 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions and Goal 14: Life below water were the least targeted. Other global frameworks Signatories frequently align with included the 2X Challenge and the Paris Accords.

- Developing a theory of change. 53% disclosed creating a theory of change or impact thesis. While a theory of change was most commonly used to establish strategic impact objectives for the fund or portfolio, theories of change were also created at many other levels (e.g., asset classes, impact themes, individual investments) and used as a tool across the investment lifecycle.

Emerging Practices

(25 to 50% of disclosures)

None identified for this principle

Nascent Practices

(<25% of disclosures)

- Establishing proportionate scale of impact. 17% disclosed explicitly assessing or considering the scale and intensity of intended impact to ensure it was proportionate to the size of the capital. This practice was more frequently observed in multilateral development banks, development finance institutions and blended finance strategies. The proportionality was often framed in terms of ambition in resource allocation, capital leverage or contribution, and considered when developing the theory of change, setting impact metrics and goals, or during assessment of investment opportunities.

Principle 1 Signatory Practice Spotlights

-

Asset Class: Private Equity

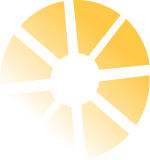

ABC Impact (ABC) invests in high-growth companies whose products and services drive positive impact in the Asia region while delivering market rate returns. Focused on investments that contribute to solutions for overarching social and environmental challenges and market gaps in the region, ABC applies robust, evidence-based theories of change frameworks at both the impact theme and individual investment levels and ensures their alignment to the SDGs. [See Practice Example 1.1]

- Scaling solutions with colinear business model. ABC’s strategy is to invest in high-growth businesses where impact outcomes are collinear with the commercial success of the companies, enabling achievement of desired impact outcomes along with a disciplined focus on risk-adjusted financial returns.

- Multi-level application of theories of change to strengthen impact management. Theories of change are developed for the fund’s overall objectives and four investment themes — better healthcare and education, financial and digital inclusion, climate and water solutions, and sustainable food and agriculture — as well as for the individual companies. This tiered approach ensures that each company adheres to the theme level theory of change, supporting alignment between impact objectives and investment activities across the portfolio.

- Evidence-based impact framework: Impact strategy for the investment themes is anchored in a robust evidence base of external studies and evaluations to validate the societal need and viability of the strategy, while company-level theories of change are grounded in business-specific insights. A proprietary Impact Measurement and Management (IMM) framework is applied across the investment process to embed impact considerations into decision making, ensuring alignment with both strategic objectives and measurable outcomes.

- Outcome and Impact measurement: Company-level theories of change link measurable outputs to relevant SDGs, with KPIs established to track contributions and overall impact post investment. Focused impact studies conducted post-investment inform and validate the impact thesis with ground-truth data.

* Signatory is Temasek Trust Asset Management Pte. Ltd., under which ABC Impact operates.

Practice Example 1.1.

ABC Impact’s Theory of Change Across Themes and Investments

Practice Example 1.2.

Core Elements of ABC Impact’s IMM Across the Investment Cycle

Asset Class: Private Debt

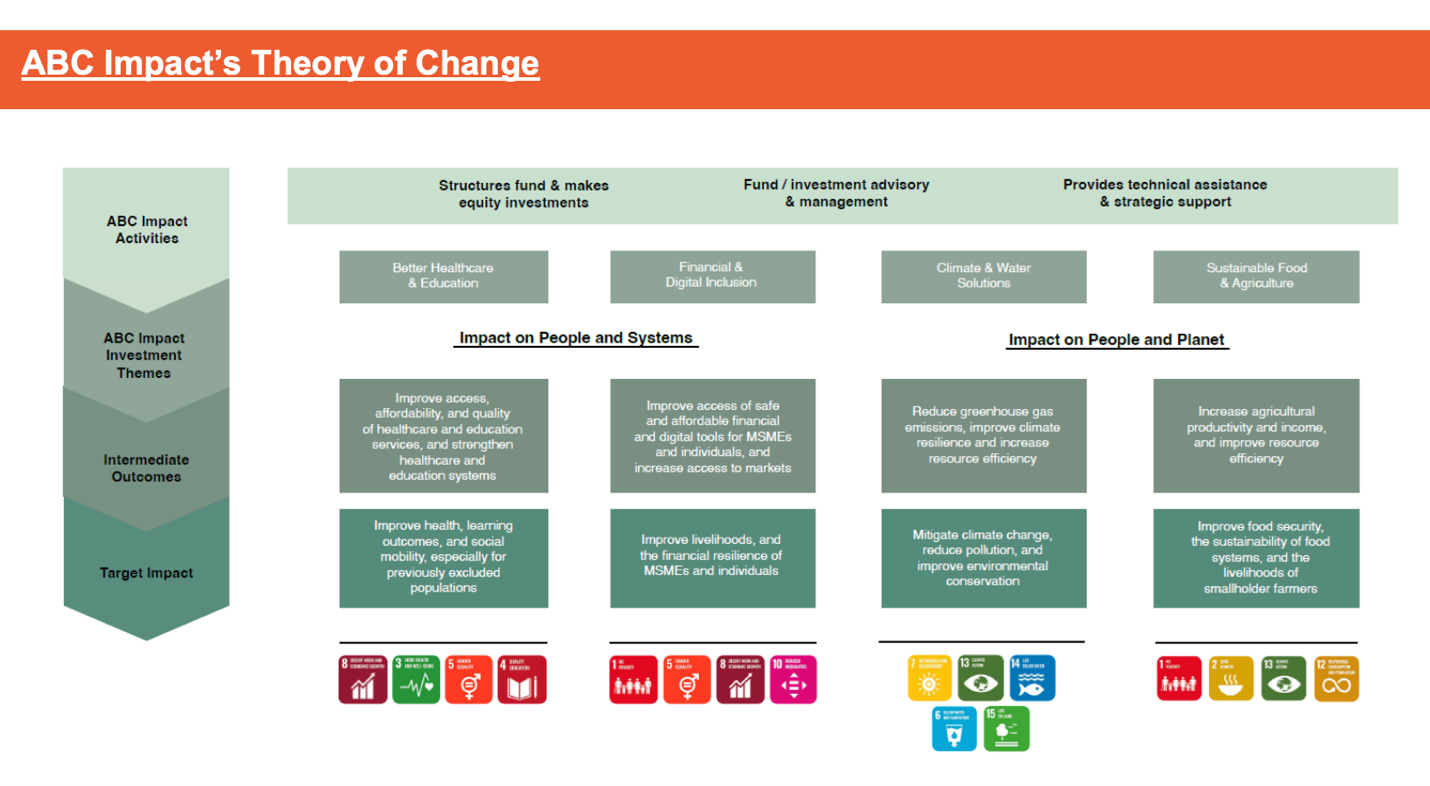

Acre Impact Capital ‘s (“Acre”) Export Finance Fund (the “Fund”) finances essential and climate-aligned infrastructure benefiting underserved populations. By investing alongside well-established Export Credit Agencies (“ECA”), the Fund addresses the estimated $100 billion annual infrastructure financing gap in Africa. Its “impact-first”, market-rate investment strategy is underpinned by a robust impact management system and an explicit theory of chance, which integrates both transaction and system level impacts.

- Closing the financing gap, catalyzing investments: Acre’s Export Finance Fund addresses the financing gap in the export finance market in Africa, which prevents the closing of bankable climate-aligned infrastructure projects. Acre funds the 15% commercial loan tranche of a transaction, which needs to be in place before an ECA can provide guarantees on the remaining 85% of the debt. By investing in the chronically underfunded 15% tranche, the Fund unlocks transactions and mobilize up to 5.6X in private sector capital.

- Impact-first, market-rate investment strategy: While being an impact first investor, Acre also targets risk-adjusted, market-rate returns, within the context of delivering meaningful impact aligned with the SDGs. Acre invests across four impact themes: (i) Renewable Power; (ii) Health, Food and Water Scarcity; (iii) Sustainable Cities; and, (iv) Green Transportation. [See Practice Example 1.3]

- Theory of change for both system and transaction level impacts: Acre’s theory of change assumes both transaction and system level impacts. Transaction-level impact pathways focus on capital mobilization, savings to borrowers and supporting the provision of essential infrastructure. At the system level, the Fund offers institutional investors access to a new impact-oriented asset class, allowing the deployment of debt capital at scale to support the development of Africa’s essential infrastructure. [See practice Example 1.4]

Practice Example 1.3.

Acre Impact Capital Strategic Impact Objectives

Practice Example 1.4.

Acre Impact Capital Theory of Change

Asset Class: Private Equity, Infrastructure

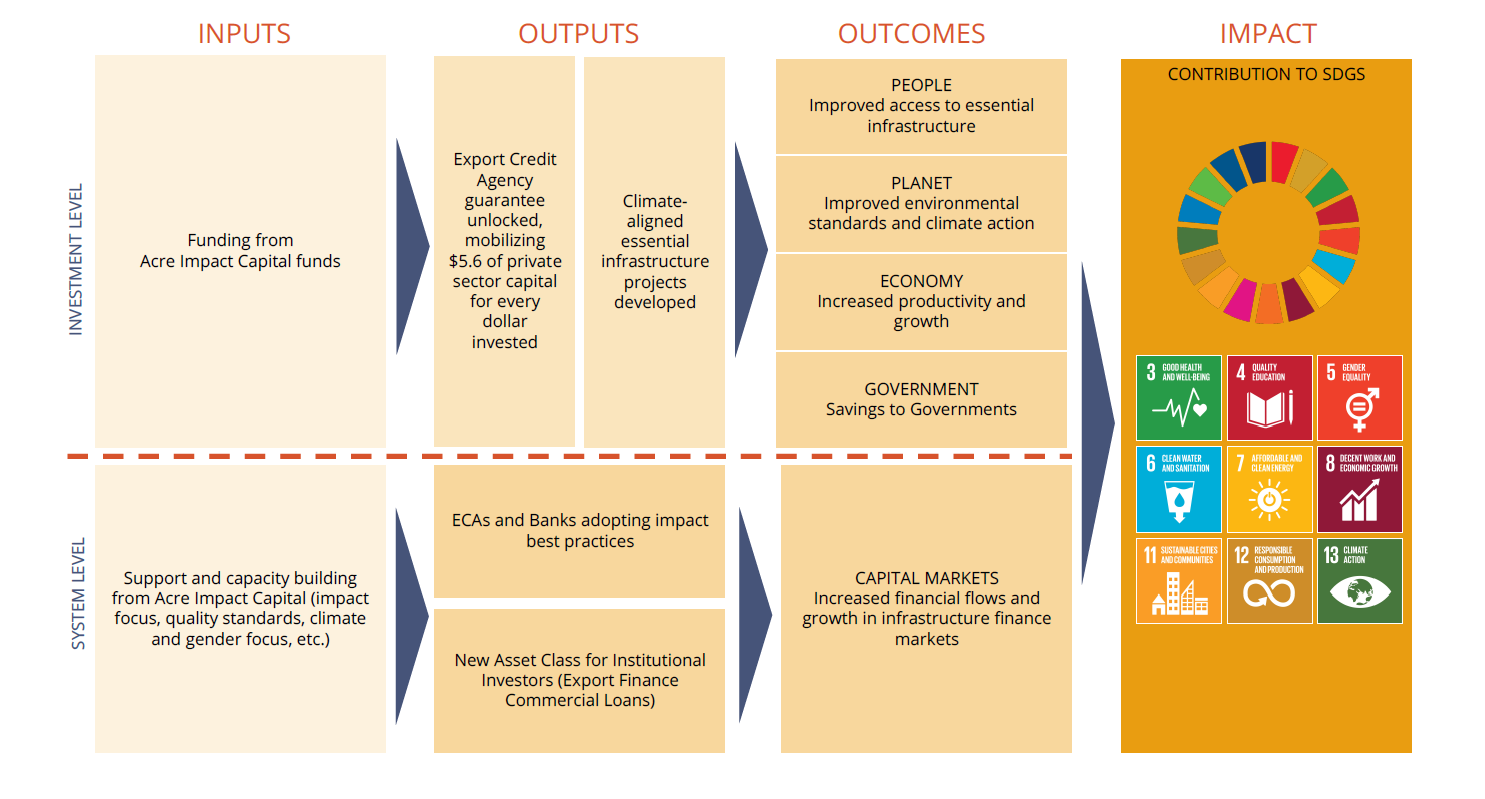

Brookfield’s renewable and energy transition funds (BGTF I, BGTF II and CTF) define a dual objective to deliver strong risk-adjusted financial returns and measurable decarbonization impact. Funds invest across clean energy, sustainable solutions and business transformation themes to accelerate the transition to a net-zero global economy in developed and emerging markets.

Key features of Brookfield’s approach include:

- Strategic anchoring on decarbonization with value creation potential: The funds target investments in high-quality assets, technologies and companies with potential to accelerate decarbonization and where Brookfield can make a measurable positive impact. Building on its platform as a leading global alternative manager, the investment strategy focuses on sectors where Brookfield has deep expertise and can enhance value through transition and active management. [See Practice Example 1.5]

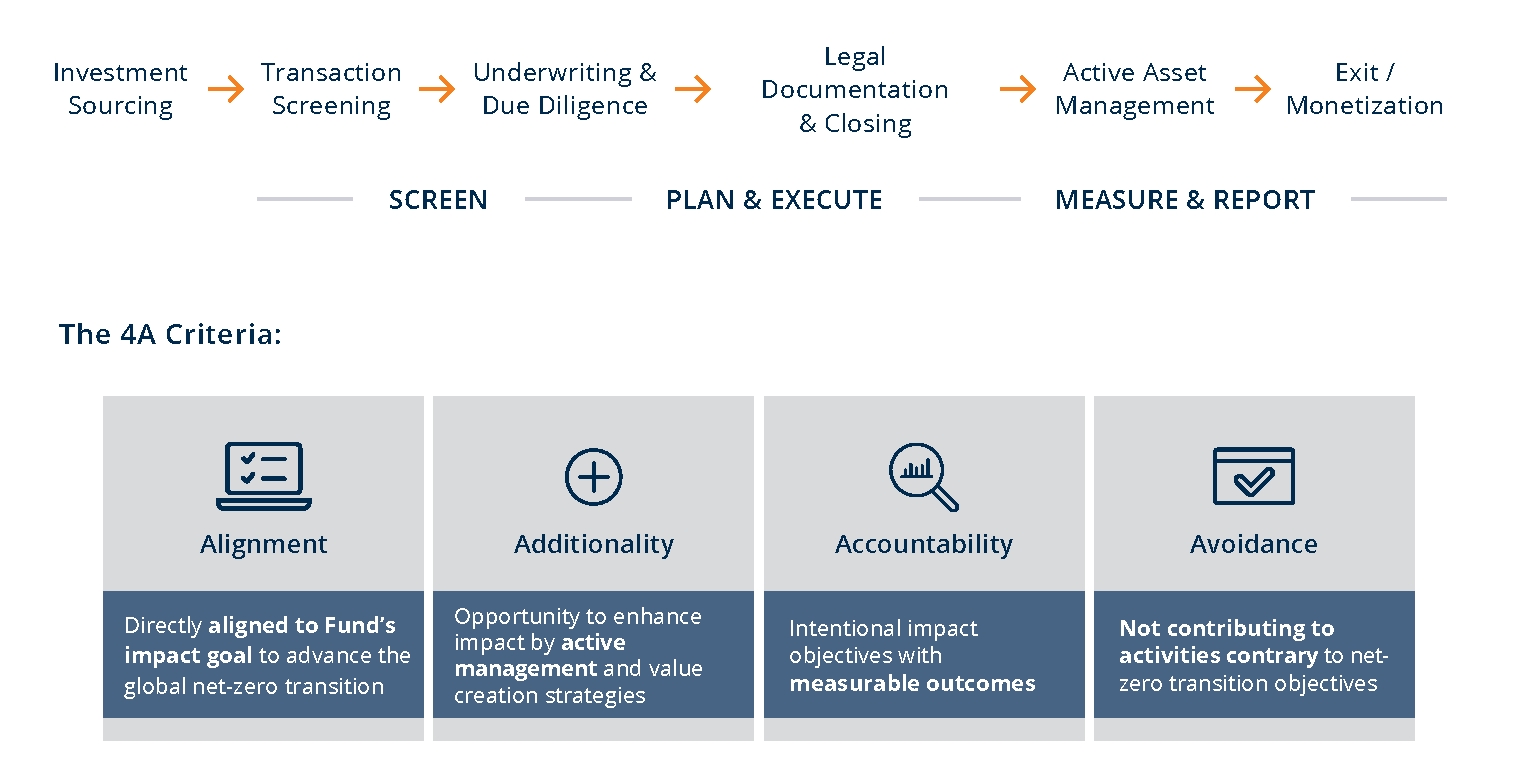

- Lifecycle integration with structured impact measurement and management, targets and reporting: Impact objectives are embedded throughout the investment lifecycle, from sourcing to exit, aligning each investment with the funds’ overarching decarbonization goals and investment strategy. Each investment is assessed against the 4A criteria assessing alignment, additionality, accountability and avoidance. For each investment, Brookfield develops a business plan, sets quantitative impact targets and reports on Scope 1, 2 and material Scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions and other relevant performance metrics. [See Practice Example 1.6]

- Contribution to global frameworks: The funds’ strategy contributes to widely accepted global goals such as the SDGs — including Goal 7: Affordable and clean energy, Goal 9: Industry, innovation and infrastructure, and Goal 13: Climate action — reinforcing consistency with industry standards and supporting broader systemic efforts toward net-zero transitions.

Practice Example 1.5.

Brookfield’s Investment Strategy

Practice Example 1.6.

Brookfield’s Impact Measurement and Management Framework

Asset Class: Multiple

Through its Sustainable Investors Fund (SIF), Capricorn supports and scales purpose-driven, early and growth-stage asset managers with innovative strategies to drive large-scale change. SIF takes minority ownership stakes (known as GP Stakes) in these firms and pairs this capital with strategic support to accelerate impact at both the firm and system levels. SIF focuses on three key impact areas: climate change mitigation & resilience, financial inclusion, and healthcare access & innovation—strategically targeting sectors where it believes specialized investment expertise can drive both financial returns and meaningful systemic change. [See Practice Example 1.7]

- System change-driven theory of change: SIF addresses the systemic challenge of capital concentration in large, established investment firms, which limits the growth of impact-aligned capital deployed by emerging managers with innovative strategies. Its four strategic pillars include:

- Identifying and investing in specialist asset management firms with potential to transform markets and create systemic impact.

- Providing hands-on support to help asset managers scale their investment strategies and raise institutional capital.

- Partnering with managers to strengthen their impact measurement and management capabilities.

- Leveraging Capricorn’s platform to advance impact standards across the asset management industry.

- Colinear model for impact and financial return: SIF approach is anchored in the belief that financial performance and impact can be aligned. Portfolio firms must demonstrate how scalable impact and competitive risk-adjusted returns are interlinked through a clear investment thesis.

- Platform-based partnership to scale high-impact models: Leveraging flexible capital and Capricorn’s network platform, SIF offers hands-on support in strategic planning, fundraising, operations and marketing — enhancing firm-level capacity and investor contribution beyond capital. It prioritizes untested, high-potential models that can create demonstration effects for the broader market, while helping to advance impact standards across the asset management industry.

Practice Example 1.7.

3 Key Focus Areas Where SIF Sees the Greatest Opportunity for Scale

Value–Added Services Provided to Investee Asset Management Firms:

Asset Class: Private Equity, Private Debt

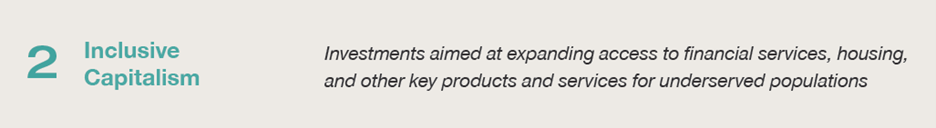

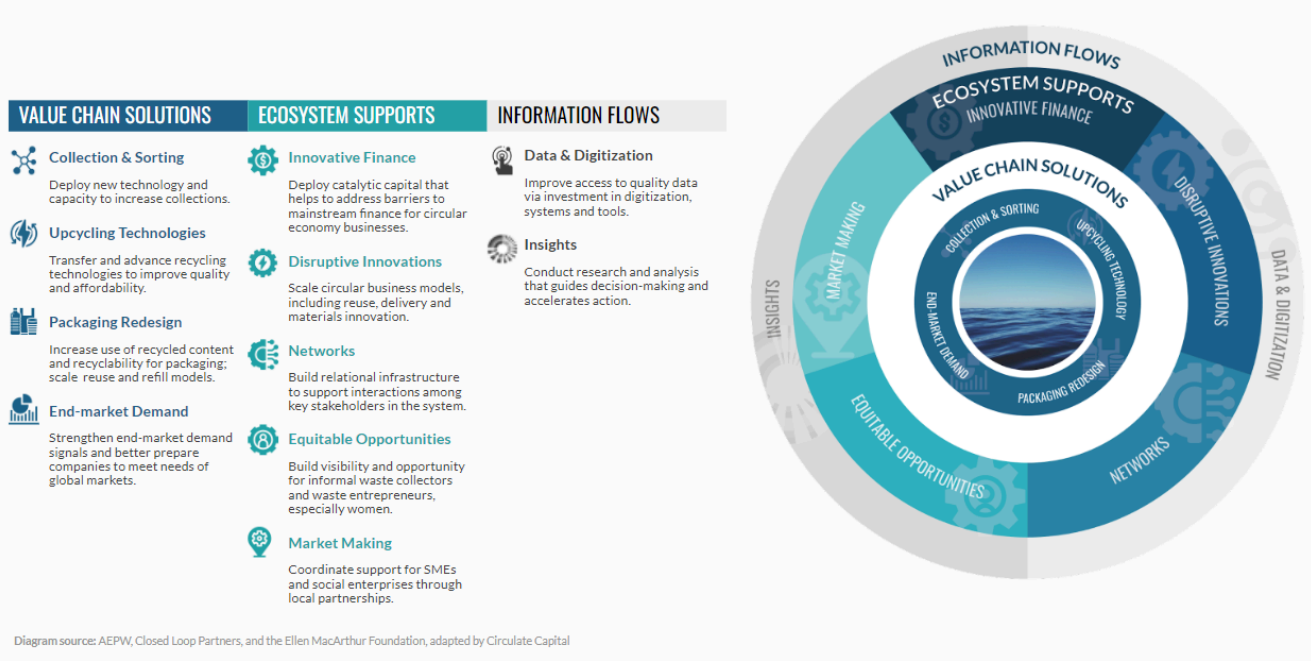

A Singapore-based asset manager, Circulate Capital invests in solutions that address plastic pollution, promote the circular economy and drive climate innovation. The firm’s strategic impact objectives are grounded in creating a visible pipeline of high-potential investments that catalyze institutional capital toward sustainable systems change.

- Catalyzing capital through demonstration: A core element of Circulate Capital’s impact strategy is demonstrating the viability of high-impact investment opportunities to attract additional institutional capital into the circular economy. This includes showcasing investable models and sharing impact results with the broader market.

- Investing across the value chain: Circulate Capital invests in solutions across the circular economy value chain, from innovative materials to advancements in recycling, accelerating a more inclusive, innovative and circular economy. The firm’s funds target four core solution areas that address current gaps in the plastics value chain:

- Disruptive innovations that advance circularity, including new materials and recycling models.

- Collection and sorting infrastructure to prevent plastic leakage and enhance recycling systems.

- Upcycling technologies to improve the value of recycled materials.

- Supply chain digitization leveraging AI, big data and deep tech for transparency and traceability.

[See practice example 1.8]

- Global alignment and engagement: Circulate Capital’s investment activities support multiple SDGs, including Goal 9: Industry, innovation and infrastructure, Goal 12: Responsible consumption and production and Goal 13: Climate action. The firm also engages with industry initiatives to develop and promote circular economy investing in the market.

Practice Example 1.8.

Circulate Capital Value Chain Approach

Circulate Capital Contributions

Asset Class: Private and Public Debt, Private Equity

Finance in Motion develops, manages and advises funds designed to generate positive social and environmental impacts in emerging markets. These funds’ strategies center on two thematic priorities: promoting a green economy by channeling capital to green sectors and promoting entrepreneurship and livelihoods by channeling capital to local businesses and low-income households. Finance in Motion targets impact on people, planet and the broader impact investing market through disciplined product design, rigorous evidence-based impact measurement and management and a commitment to catalytic solutions.

- Fund-specific, evidence-based impact strategies: Each fund has a theory of change and clearly defined impact objectives that are both aligned with Finance in Motion’s impact objectives and tailored to its thematic and geographic focus. During the creation of new funds, market research and stakeholder mapping contribute to the development of locally relevant approaches, and the selection of impact measures is supported by documented evidence of effectiveness.

- Alignment with global sustainability frameworks: Finance in Motion’s funds map their activities to SDG targets to identify and report on their contributions to global development. All funds align with the climate goals of the Paris Agreement and report in line with Article 9 under the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation.

- Impact on markets and systems: The theory of change considers both the direct impact on the investee as well as the indirect, systemic impacts on or through the investee’s end-clients. Finance in Motion contributes to the scaling of the impact investing market with integrity by providing dedicated financing and technical assistance, mobilizing public and private capital through blended finance structures, and conducting thought leadership and community-building activities that enable investors to make high-quality impact investments in emerging markets. [See Practice Example 1.9]

Practice Example 1.9.

Finance in Motion’s Pathway to Impact

Asset Class: Multiple

As a member of the World Bank Group (WBG), the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency’s (MIGA) mandate is to promote the flow of foreign investment to developing countries by providing guarantees against non-commercial risk to investors, including lenders. The guarantees, which address risks such as currency inconvertibility, expropriation, breach of contract and conflict-related risks, offer a range of benefits to investors seeking protection and continuity for their projects in developing markets. Anchored in the WBG’s broader vision of creating a world free of poverty on a livable planet, MIGA integrates impact considerations from early project screening to final approval. It does so using its proprietary IMPACT system to assess and prioritize transactions with the highest potential for transformative development outcomes.

- Catalytic capital for protection and continuity: MIGA helps investors mitigate the risks by providing political risk insurance, credit enhancement on sovereign and sub-sovereign financial obligations and trade finance guarantees, against government or state-owned enterprise failure to make a payment.

- Development impact: The Impact Measurement and Project Assessment Comparison Tool (IMPACT) system is MIGA’s project impact assessment tool. It estimates the expected development impact of its interventions at their initial stage and assigns ex-ante development impact ratings aligned with country-specific development gaps. [See Practice Example 1.10]

- Cross-institutional alignment and sectoral focus: MIGA aligns with WBG Country Partnership Frameworks to prioritize focus areas and resource allocation for country-specific development impact. It leverages diagnostic and analytical work to identify constraints and opportunities for private sector guarantees.

Practice Example 1.10.

MIGA’s Overall IMPACT Expected Score and Rating

Asset Class: Multiple

Nuveen applies a firm-wide impact approach across its diverse portfolio spanning multiple asset classes — private equity, fixed income, real estate and private debt. Each strategy defines a set of impact themes and guidelines to ensure that the investments align with those themes, drawing on internal expertise and third-party research linking the investment activities to impact objectives.

While each asset class follows a distinct investment model, all strategies are guided by a shared commitment to delivering measurable social and environmental outcomes aligned with the SDGs. As of 2024, Nuveen’s collective strategies align with SDGs 1 through 16. [See Practice Example 1.11]

- Fixed income: The Global Fixed Income Impact strategy focuses on directing capital based on use of proceeds and targeted social and/or environmental outcomes. While the impact framework – launched in 2007 – predates the SDGs, it now maps the impact themes to SDG targets through defined outputs and outcomes.

- Private equity: The Private Equity Impact Investment strategy targets transformative companies that are disrupting value chains to reduce waste, mitigate climate change, or serve low-income consumers. An impact thesis is developed prior to closing each investment, outlining expected results and SDG alignment.

- Real estate: The US Real Estate Impact strategy combines environmental objectives with community-driven outcomes. Investments include property-level initiatives such as resident services and programs (e.g., health and well-being, housing stability, financial education) and climate resilience and sustainability upgrades tailored to building type and location.

- Private credit: The Impact Lending Strategy provides debt to businesses contributing to goals in climate, health, education, and economic inclusion. Each theme is supported by defined sustainable objectives and tracks contributions to targeted outcomes.

Practice Example 1.11.

Nuveen’s Impact Themes and SDG Alignment by Asset Class

Asset Class: Private Equity (Venture Capital)

SIIFIC applies a systems change-driven investment strategy centered on four themes that target structural levers of wellness with a regional focus in Japan: revolutionizing healthcare, empowering holistic well-being, connecting lives and cultivating local prosperity. Together, these themes aim to transform not only individual outcomes but the social, behavioral and economic systems that shape lifelong well-being.

- Holistic definition of wellness equity: Wellness is framed as a state of physical, mental and social well-being — not limited to the absence of disease — requiring multi-sectoral change to improve quality of life and reduce disparities.

- SDG alignment through a local lens: Investments are linked to SDGs 3, 8 and 11 to align with a global framework, while also reflecting national priorities through Japan’s SDGs Action Plan and the Digital Agency’s Regional Well-Being Index. This dual approach enhances both global relevance and regional applicability.

- Theory of change driven approach and system mapping: SIIFIC’s investment approach is bolstered by a theory of change that emphasizes wellness literacy and social capital. For each investment, SIIFIC develops a comprehensive system map which facilitates creation or refinement of its theory of change and serves as the foundation for outcome-based impact KPIs and impact strategies based on an understanding of the complex ecosystems. [See Practice Example 1.12]

- Framework used across the lifecycle and Principles: The system mapping and theory of change guide investment decision making across the lifecycle for SIIFIC, by clarifying contribution (Principle 3), assessing expected impact of investments (Principle 4), identifying risks (Principle 5), and refining processes and promoting field learning (Principle 8).|

SIIFIC demonstrates how systems thinking can be operationalized through robust, context-specific impact frameworks — linking global goals to national priorities and advancing long-term transformation toward wellness equity.

Practice Example 1.12.

SIIFIC System Map Example: The Current State of Social Capital in Local Areas